Guardians or Gatekeepers? India’s Data and Telecom Laws Empower the State

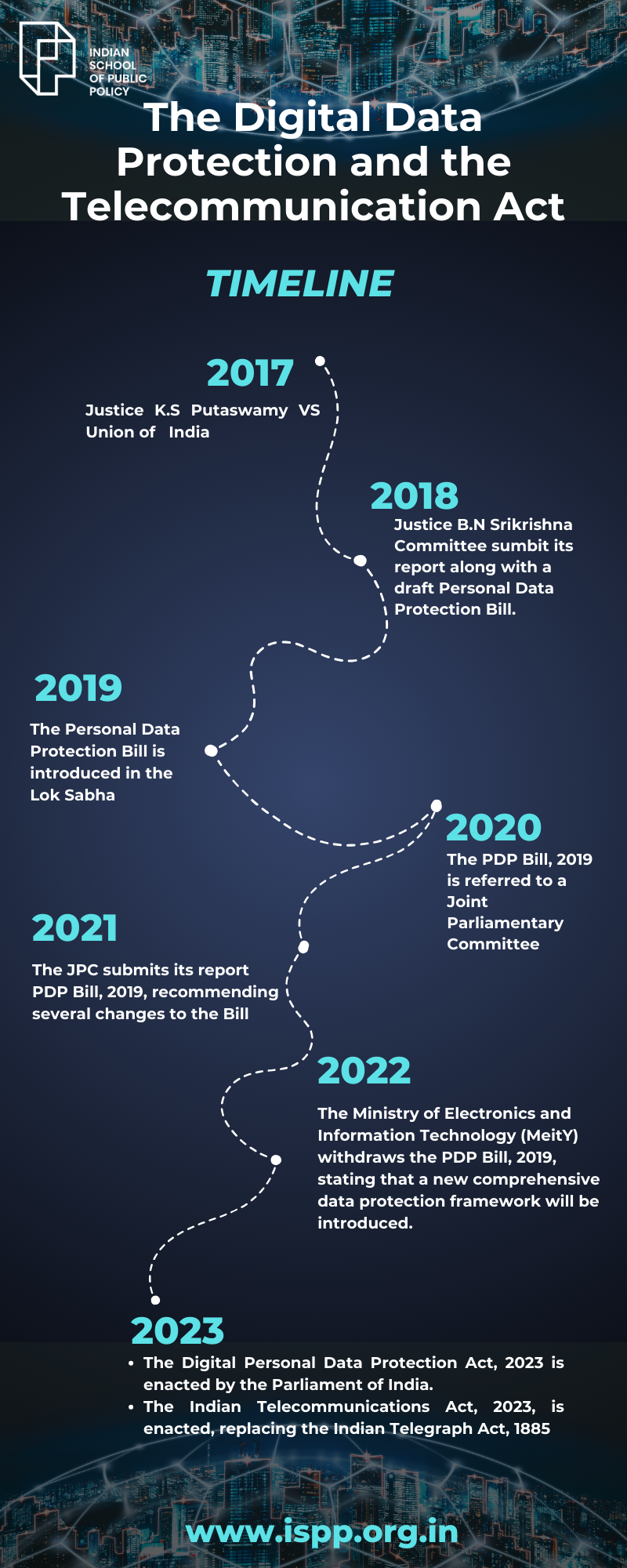

In 2017, a historic judgement was delivered in the case of Justice K.S Puttaswamy VS Union of India. The nine Judge Bench unanimously affirmed that the right to privacy is a fundamental right and an attribute of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. However, the court’s judgement highlighted the absence of a precise “doctrinal formulation, 1” leading to various drafts over the years, and seven years later, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act was passed in Parliament. The Act was introduced with the primary objective of balancing the rights of individuals to safeguard their personal data and the necessity to process such data for lawful/authorised purposes. The legislation passed another bill called Telecommunication with aspirations to leave our colonial roots behind by seeking to replace the Telegraph Wires (Unlawful Possession) Act 1950, the Indian Telegraph Act 1885, and the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act 1933. The act aims to provide a modernised framework to aid the growth and advancement of the telecommunications sector. This paper argues that the DPDP Act and Telecommunication Act vow to be a legal framework for protecting an individual’s rights. Still, the ground reality is that these acts centralise power to the government to the extent that the rights of citizens hang in the balance, losing sight of the objective.

The Data Protection Board, a regulatory body tasked with overseeing and imposing the provisions of the DPDP Act, is not an independent body but rather under the government’s monopoly. The Board is merely an extension of the government’s authority and control because, in reality, its composition, procedures, and critical powers are effectively under the supervision of the government. A substantial degree of power is vested with the central government, and the Data Protection Board lacks the autonomy to function effectively as an unbiased system, limiting its ability to hold government and private entities accountable for data protection violations, exempting itself and other government instrumentalities from the purview of the law when it is contingent on “interests of sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, maintenance of public order or preventing incitement to any cognisable offence relating to any of these.2” Leaving behind endless loopholes and a lack of accountability in favour of the Central Government. To illustrate, section 19 of the bill empowers the Central Government with expansive powers of appointing the Chairperson and other board members. Through this provision, the Central Government can regulate the power of the Board, which defeats the purpose of establishing an independent regulatory body. Section 17 of the bill bestows the Central Government with the power to exempt any of its instrumentalities from core provisions of the Act by simply issuing a notification. Section 40 of the bill gives the Central Government extensive rule-making powers over numerous issues enumerated. By bestowing the government with rampant powers to the extent that there is a great margin for violating an individual’s fundamental right to data privacy, ironically promoting the very notion of what this act set out to protect.

It is a paradoxical situation wherein two fundamental rights, “the right to information and the protection of life and personal liberty 3”, struggle to find a balance. The Right to Information Act, Section 8(1)(j) allows the disclosure of personal information if it serves a larger public interest. According to this bill, Section 8 (1)(j) of the RTI Act will be removed, abolishing the notion of disclosure in the general public’s interest. This is confirmation that the government has chosen to side with the data protection of individuals over transparency rather than striking a balance between the two. The Right to Information Act has been in place for 17 years. Informed citizens with the power to question, scrutinise, and hold the government accountable and expose corruption and unjust practices is an important milestone in the history of Indian democracy. It has contributed immensely to building transparency between the government and its citizens. For example, the Right to Information (RTI) Act was pivotal in resolving the grievances of pensioners and legal heirs who had not received their rightful payments from the Directorate of Pensions and by filing an RTI application seeking details on returned pension cheques, S Rajendran, the District Treasury Officer, facilitated the disbursement of Rs 1.5 crore to 327 individuals who had been awaiting their dues. However, by amending the act, such information could potentially be withheld on the grounds of being related to the personal information of pensioners 4. This would undermine the transparency and accountability that the RTI Act aims to foster, and it will only derail all the progress that we have made so far, marking this as a regressive act.

The RTI isn’t a standalone bill passed by the government that aims to curtail our right to privacy, but there are other acts passed with the same end goal in mind. Namely, Telecommunication Bill 2023 was introduced in the Lok Sabha to modernise colonial laws and keep pace with the rapidly evolving technology space. The Telecommunication Bill 2023, however, seems to still be under the clutch of colonial provisions of 1885. This act appears to endow the government with extensive power at the expense of individual rights. Its vague description of telecom services could potentially cover online communication services such as email, cloud services, and online service platforms that are traditionally left out. It leaves sweeping control to the executive to interpret what telecom services will entail. One of the most concerning aspects is the authority granted to the central and state governments to seize control over any telecom network or service under vaguely defined terms of “public emergency” or “public safety.” Such ambiguous language can lead to officials’ misuse of this broad provision.

Furthermore, the bill empowers government personnel to indiscriminately detain, intercept, or prohibit the transmission of messages from persons or groups of people. This single invasive provision gives the government endless leeway for nationwide pervasive communication surveillance and censorship. The proposed bill also mandates biometric authentication and the forcible identification of every single social media/ internet user’s credentials under a KYC framework. This encroachment of anonymity will make targeted monitoring and immobilisation of opposition and minority groups an easy possibility for the government. The government’s involvement in setting up security provisions for telecom services is concerning in light of the government’s desire to undermine the encryption of WhatsApp and Signal. This controversial bill was passed in both houses of the Parliament in the absence of opposition party members and amidst concerns of privacy infringement and the government’s radical control over private communication.

At first glance, these seem like two unrelated events, but if we keenly observe, we notice that the government is very subtly, or not so subtly, pushing forth its agenda of building a government modelled after totalitarianism and is representative of a deliberate tectonic shift in government policy. The key beneficiaries of the DPDP Act are the Central Government and the Executive, with little regard for safeguarding the interests of citizens. This deliberate move by the government alludes us to the fact that their primary goal here is data protection and regulation of personal data in the hands of the government itself, rather than upholding an individual’s right to privacy and transparency or access to information to citizens, even in the case of public servants. Likewise, the Telecommunication Act formulated to replace an archaic law seems to be even more old-world, the basis of its objective being “to ensure that there is freedom of speech but no guarantee of freedom after speech.” These acts, with robust mechanisms and stringent provisions, were put in place with the primary goal of safeguarding the rights of individuals. But, has the executive lost sight of the end goal, or was that their intent all along? We can’t afford to be in the dark and mindlessly comply with rules without knowing what’s at stake here because these acts give enough free rein to the government to interpret the provisions as they wish, leaving the severity of these acts to the discretion of the elected government for that term. So, as citizens, we need to be well-informed about the laws and regulations that govern us and then ask ourselves the aforementioned questions. The commonality in both the Acts that I discussed lies in the fact that the government has gradually been removing slivers of our rights to add to its invasive control over us as citizens. Look for yourself, and you will notice that these Acts are symbolic of a disturbing pattern—a steady march towards an increasingly authoritarian, totalitarian style of governance that undermines civil liberties and citizen privacy.

Register your Interest to Study at ISPP

Infographic:

Works Cited:

1Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Anr. vs. Union of India & Ors.

privacylibrary.ccgnlud.org/case/justice-ks-puttaswamy-ors-vs-union-of-india-ors.

2 Malhotra, Gayatri. “India’s data protection law does little for privacy while bolstering

the state’s surveillance powers.” Scroll.in, 26 Sept. 2023,

scroll.in/article/1054722/indias-data-protection-law-does-little-for-privacy-while-bolsteri

ng-the-states-surveillance-powers.

3 How the ‘strict’ Data Act is diluting RTI.

www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/governance/how-the-strict-data-act-is-diluting-rti-91640.

4 Gandhi, Shailesh. “Ten instances show how the digital data protection bill will undermine the

RTI Act.” Scroll.in, 5 Feb. 2023,

scroll.in/article/1042602/these-instances-show-how-the-digital-data-protection-bill-will-undermi

ne-the-rti-act.

Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 | Ministry of Electronics and Information

Technology, Government of India.

www.meity.gov.in/content/digital-personal-data-protection-act-2023.

“ Understanding India’s New Data Protection Law.” Carnegie India,

carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/10/understanding-indias-new-data-protection-law?lang=¢

“‘Regressive Amendments to RTI Act’: NCPRI Flags Concerns Over Digital Personal Data

Protection Bill.” The Wire,

thewire.in/rights/regressive-amendments-to-rti-act-ncpri-flags-concerns-over-digital-personal-dat

“Telecommunications Bill Lays the Ground for Totalitarian Control of the Internet.” The Wire,

thewire.in/tech/telecommunications-bill-lays-the-ground-for-totalitarian-control-of-the-internet.

“With Cleverly Drafted Telecom Bill, Government Tightens Grip on Digital India.” The Wire,

thewire.in/government/cleverly-drafted-telecom-bill-government-tightens-grip-digital-india.

Bhalla, Vineet. “Telecom Bill increases government control of the internet, warn experts.”

Scroll.in, 23 Dec. 2023,

scroll.in/article/1060973/telecom-bill-increases-government-control-of-the-internet-warn-experts

Ritanya Mukund

Ritanya Mukund, is an undergraduate pursuing a dual degree in Data Science and Computer Science from Krea University. She is currently interning at the Indian School of Public Policy, where she applies her analytical abilities to address real-world public policy challenges. Her liberal arts education has cultivated a holistic mindset, enabling her to integrate diverse perspectives into her work. Her unique blend of technical expertise and multidisciplinary approach positions her well for a career in driving data-driven policy solutions.