Exploring Determinants of Insurgency-Related Casualties in Northeast India, 2000-2019

Abstract

How do economic growth, enhanced inclusion and participation in national-level politics, and majority support for ethnic rebel outfits impact the human cost of insurgencies in India’s Northeast region (NER)? Exploiting panel data of the ‘Seven Sister’ states from 2000-2019, I employ Poisson fixed-effects regression models to analyse these relationships. To address endogeneity concerns, I leverage rainfall variability as an instrumental variable (IV) for economic growth. To execute this IV strategy, I conducted a two-stage control function procedure. The empirical results reveal that economic development is associated with a reduction in incidents of casualties resulting from insurgent activities, corroborating Gurr’s theory of relative deprivation (1970). Moreover, enhanced national-level political participation, as proxied by the number of questions asked by Members of Parliament (MPs) from the Northeast states pertaining to regional development and tribal affairs, was not found to decrease the human cost of insurgent activities in the IV models. On the other hand, the inclusion of MPs from these states in the Union Council of Ministers significantly decreases incidents of fatalities. Furthermore, majority ethnic group support for rebel groups is positively related to incidents of killings, underscoring the significance of addressing community support to alleviate insurgency-related violence. The findings provide insights for policymakers and stakeholders in designing effective strategies to mitigate the impact of insurgencies and promote peace and development in the region.

Keywords: Insurgency, deprivation, development, inclusion, participation.

Introduction

India’s northeast region (NER) comprises the ‘Seven Sisters’, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura, with Sikkim added after its annexation in 1975. The region is geographically positioned as a bridge between South Asia and the Indochinese Peninsula and is characterized by dense forests, hilly topography, and the presence of the Brahmaputra river system. The only link between NER and mainland India is the Siliguri Corridor, a twenty-kilometre wide stretch flanked by the eastern Himalayas and the India-Bangladesh border. This, coupled with the fact that ninety-eight per cent of the NER’s borders are international, makes the area difficult to manage for the Central and State governments (Government of India, 2008). Despite sharing cultural motifs, expressions, and practices, NER is not a monolithic region. As Bhaumik (2004) stated, ‘it is a polyglot region, its ethnic mosaic as diverse as the rest of the country’. The Anthropological Survey of India’s ‘People of India’ project in 1985 found that 213 of India’s 635 tribal communities were located in NER, along with 175 languages from the Tibeto-Burman and Mon-Khmer families (ibid).

During the British Raj, NER was governed indirectly through native leaders. Assam alone was treated as an imperial province due to British investments in tea, timber and oil. The British had a ‘peripheral interest’ in the NER, viewing it as a ‘buffer’ between the Bengal plains and China-Burma highlands (Baruah, 1989). The region, therefore, exercised some autonomy as long as the British suzerain wasn’t threatened. Haokip (2012) argues that this British policy of neutrality in the region estranged the hill tribes from the Indian freedom struggle. After India’s independence, attempts to incorporate NER into the national mainstream faced resistance from the local population, who identified more with their ethnic communities than as Indians (Cline, 2006). The ‘Seven Sisters’ have all since witnessed copious insurgent activity; Manipur has the sobering distinction of being the most insurgency-prone state in NER, with almost 40 per cent of NER’s insurgency activities between 2000 and 2019 taking place there. Sikkim alone has hitherto remained unscathed. Figure 1 illustrates the number of terrorism-related incidents that occurred in the ‘Seven Sisters’ between 2000 and 2019.

Figure 1: Number of terrorism-related incidents in NER, 2000-2019

In an attempt to ameliorate violent insurgencies in these ‘disturbed areas’, the Government of India passed the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA). The Act has been operational in the region since 1958 and is still in place in various districts of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur and Nagaland. It was repealed entirely in Mizoram since the 1980s, Tripura since 2015, and in Meghalaya since 2018. Bhattacharya (2018) said of the Act, ‘the legislation bestows sweeping powers and impunity to forces for all crimes (including rapes and gang rapes) in the name of counter-terror operations’. Their ethnographic research investigated how AFSPA intensifies the sense of alienation of the ‘marginal’ NER from India’s ‘core’, legitimizes violence and reinforces militant, insurgent outlooks within the region.

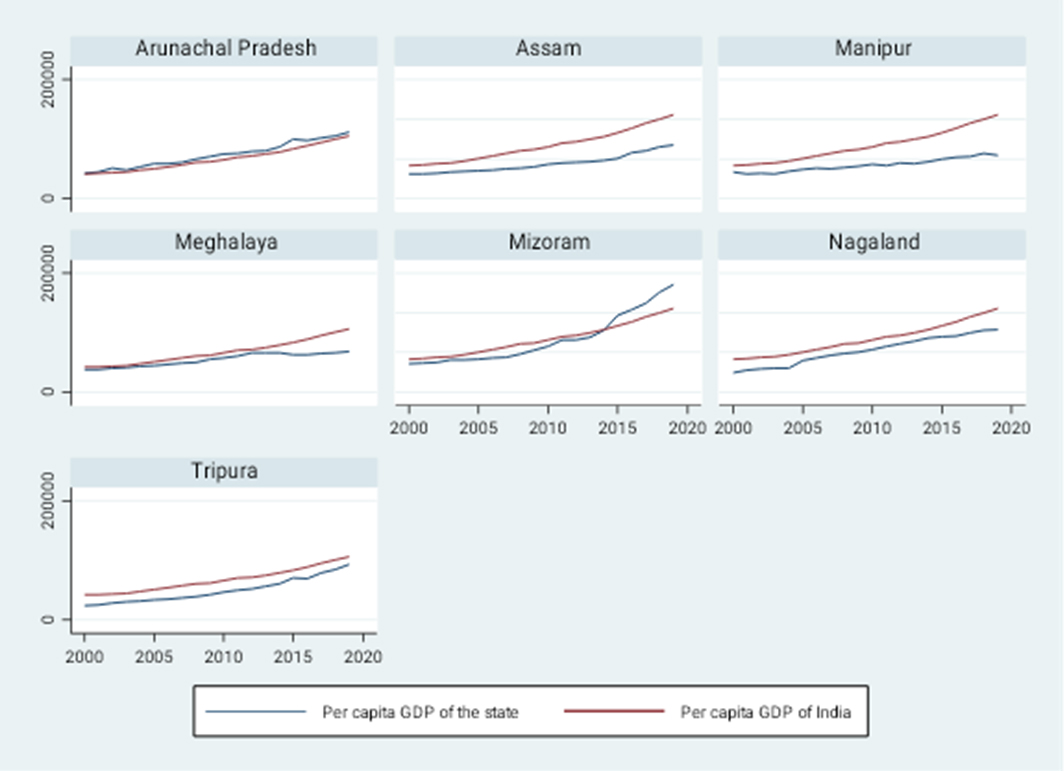

Therefore, a reading of NER’s history suggests that factors such as; (i) their geographic and ethnic ‘othering’ from ‘mainland’ India, (ii) the intra-regional ethnolinguistic fractionalization, (iii) their unique history that diverges from the “national canon”, and the post-colonial Indian government’s insufficient attempts to mainstream NER’s distinct social and economic characteristics in their development strategies, and (iv) the Central government’s enforcement of draconian counter-insurgency measures under AFSPA, among others, have contributed to an insurgency in NER. All of these forces have also worked in synergy to create the conditions of material and socio-political deprivation in the area that persist to this day. Figure 2 shows the growth of the ‘Seven Sisters’ states in comparison to aggregate India. Except for Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram (the two states least affected by insurgency out of the seven), all other states have had a consistently lower per capita GDP from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 2: Comparing per capita GDP of the “Seven Sisters” with India’s per capita GDP, 2000-2019

This relative underdevelopment manifests in the lack of industrialization and infrastructure, high unemployment, and high poverty. Gurr’s theory of relative deprivation (1970) suggests that groups who experience relative deprivation are more likely to resort to political violence as a means of expressing their dissatisfaction and seeking redress. In economically marginalized settings, the opportunity cost of rebelling may be lower than that of more developed counterparts, as the economic benefits of not rebelling may be lower. This can enhance support for ethnic rebel outfits, make recruitment easier, and compel disadvantaged groups to rebel. Gurr (1994) suggests that systemic poverty and deprivation hinder the state’s capacity to handle ethnopolitical tensions, raising the likelihood of conflict in more marginalized areas. This aligns with Skocpol’s (1977) institutional theory of social revolutions, which contends that inadequate institutions result in power vacuums that ethnic rebel groups exploit, resulting in political violence.

Against this theoretical background, this paper shall attempt to quantitatively determine whether economic development would lead to reduced incidence of political violence in the region, ceteris paribus. Empirical literature pertaining to political violence in NER is scant. Vadlamannati’s (2011) panel analysis of NER states from 1970 to 2007 found that the increased poverty rate of the states relative to the national level is associated with a higher risk of armed conflict in the region. However, they did not find a statistically significant relationship between per capita Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) and the likelihood of armed conflict using a systems-GMM approach. Brahmachari’s (2019) panel study from 1990 to 2016, found that an increased Net State Domestic Product reduced the likelihood of conflict while the per capita income growth rate had no statistically significant effect. Both studies used a dichotomous outcome variable, which assumed the value 1 if the state-year experienced a civil conflict with 25 or more deaths and 0 otherwise. Ashraf and Viswanathan (2022) demonstrated that higher per capita income is associated with fewer insurgencies in the region when employing the negative binomial regression technique on data from 1980 to 2017.

This study explores Gurr’s thesis in the Seven Sister States from 2000 to 2019, aiming to contribute to the existing analysis of the research question in the NER in two ways. First is through the selection of an outcome variable, which is the number of incidents of killings through insurgencies in a given state year to refine our analysis of the human cost of insurgencies. The second value addition of this paper is how it addresses potential endogeneity concerns stemming from the bi-directional relationship between economic development and the frequency of insurgencies using an instrumental variable (IV) approach. As I have hypothesized that economic deprivation can compel conflict, I also recognize that conflict can simultaneously cause disruptions to economic activity, reduce investments, and damage infrastructure. This could lead to a simultaneity bias, thereby producing deceptive estimates of the impact of economic development on the incidence of fatalities due to insurgencies. Additionally, omitted variables such as corruption can influence both economic outcomes and occurrences of insurgencies. To extenuate these issues, I shall use exogenous rainfall variation as an instrument for economic growth, drawing from the work of Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti (2004), henceforth referred to as MSS. MSS used annual rainfall growth as an instrument to induce exogeneity in economic growth when investigating its relationship with the likelihood of conflict in Africa. However, I will be measuring rainfall variability through how many relative standard deviations the rainfall of a given state year is away from the mean annual rainfall for a state during the study period. This strategy could offer advantages that annual rainfall growth might not be in the context of the NER, which experiences significant variations in rainfall patterns across time both within and across states. This instrument captures the relative deviation of rainfall patterns for a specific state year, accounting for the unique climatic conditions and vulnerabilities of each state.

Additionally, the insulating effect of colonial British governance on NER’s visibility in national politics has had seismic ramifications still felt to this day. According to the Ethnic Power Relations (EPR) Core dataset, Hindi-speaking people have held the status of ‘Senior Partners’ in the central government throughout post-independence India, while Assamese people have been designated as ‘Junior Partners.’ Conversely, linguistic groups such as Manipuri, Naga, Bodo, Indigenous Tripuri, and Mizo populations are classified as ‘Powerless,’ indicating a lack of political influence at the national level. The corpus of conflict literature supports a positive association between political exclusion and violence (Cederman, Wimmer, & Min, 2010; Piazza, 2012). However, the impact of NER’s political inclusion and participation in national-level politics on insurgencies in the region remains an underexplored area of empirical research, which this paper aims to uncover. Here, I define ‘inclusion’ based on whether a state year has at least one Member of Parliament (MP) in the Union Council of Ministers, the highest executive body of the Government of India. ‘Participation’ is measured by the number of questions asked by MPs from NER in a given state year pertaining to Northeast development or tribal affairs during the allotted ‘Question Hour’ in Indian parliamentary proceedings.

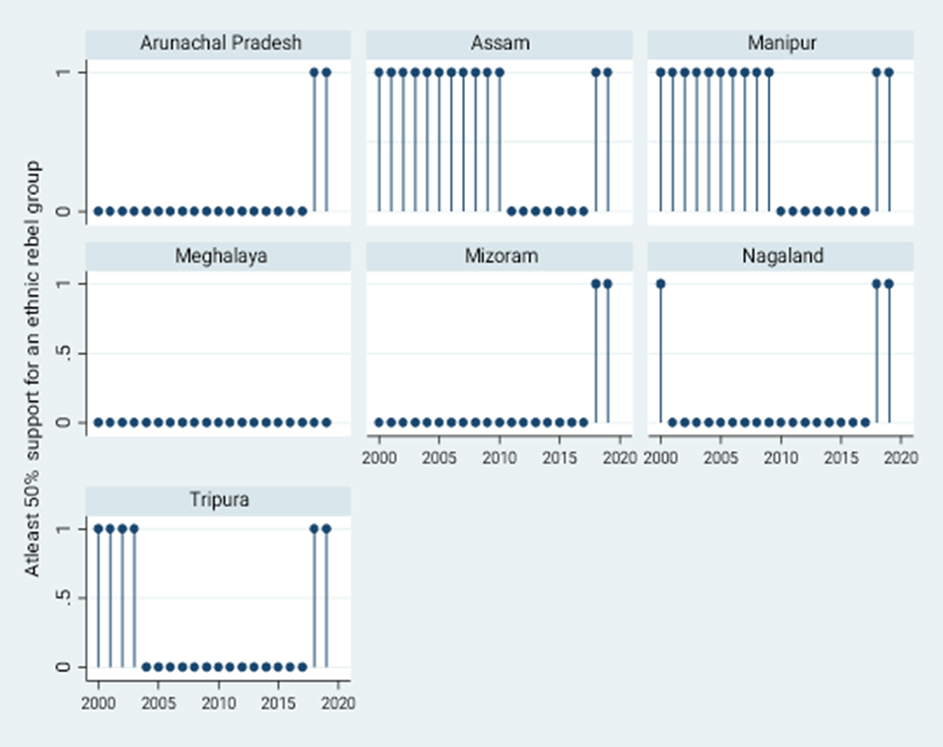

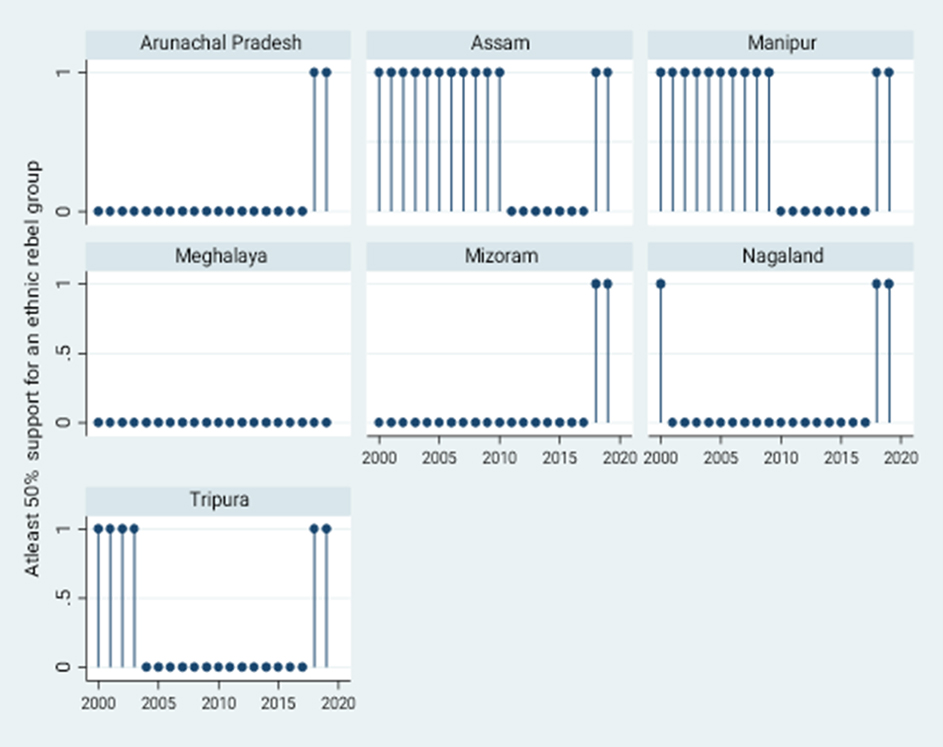

Finally, Laqueur (1999) points to the insurmountable volume of case studies that stress political exclusion as a galvanizing agent for community support for domestic terrorism movements. Community support for insurgent outfits has been a cause for concern in NER states over the study period, as demonstrated by Figure 3. Exploiting the EPR dataset, this paper postulates that high levels of community championing of ethnic rebel groups leads to increased incidence of insurgency-related casualties.

Figure 3: Years in which there exists at least one ethnic rebel group which has received atleast 50% support from the ethnic population, 2000-2019

Note: The variable is coded 1 if there exists at least one ethnic rebel group in the given state in a given year that enjoys at least 50% support from the ethnic group they represent. It is coded 0 otherwise.

Empirical strategy

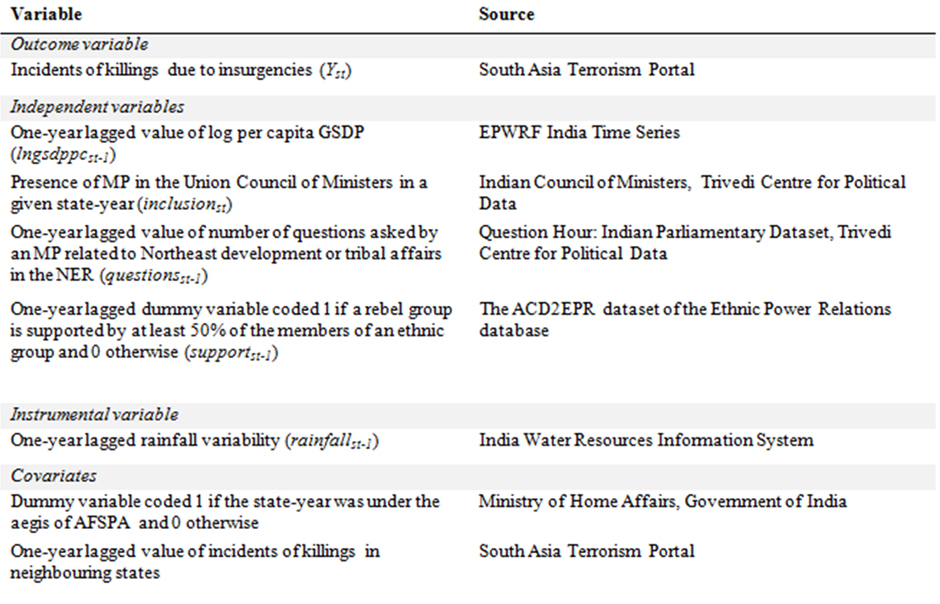

The data description and sources are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: List of variables

Given our outcome variable, the estimation of a count model is suitable. Despite evidence of ‘over-dispersion’ in the count data indicating that a panel negative binomial regression analysis is apposite, Wooldridge (1999) argues that a Poisson regression with fixed-effects (FE) is still preferable as it produces consistent estimates of relevant parameters. Therefore, I will leverage the panel Poisson method with state fixed-effects and robust standard errors, the latter to exclude the effects of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity.

I operationalize a baseline model in the form of:

Yst=?+?1*lngsdppcst-1+ ?2*inclusionst+ ?3*questionsst-1+ ?4*supportst-1+Xst?+?s+?st

(1)

Where s is the index of states, t is the index of years from 2000 to 2019. Xst is the vector of time-variant covariates and ? is the corresponding vector of coefficients. The fixed effects for state s are denoted by ?s, and ?st is the error term. I use one-year lagged values of lngsdppc, questions, and support to minimize any simultaneity bias or reverse causality that might arise from incidents of insurgency-related killings contemporaneously affecting these variables.

In order to implement the IV approach, I follow the two-stage control function procedure outlined in Wooldridge (2010). In the first stage, I regress lngsdppc on rainfall and the rest of the explanatory and control variables using panel linear regression.

lngsdppcst=?+?1*rainfallst+ ?2*inclusionst+ ?3*questionsst+ ?4*supportst+Xst?+?s+?st

(2A)

In 2A, if the estimated coefficient on our instrument π’1is statistically significant, the instrument meets the ‘relevance’ criterion. This means that rainfall variability is sufficiently correlated with the endogenous variable lngsdppc. In the second stage, the lagged estimated residuals (?’st-1) from 2A are added as an additional explanatory variable to the base model. This variable controls for endogeneity in the model.

Yst=?+?1*lngsdppcst-1+?*?’st-1+?2*inclusionst+?3*questionsst-1+?4*supportst-1+Xst?+?s+?st

(2B)

Additionally, the estimated coefficient on the control variable ρ’ provides a useful test for endogeneity; if it is statistically significant, then our premise that per capita income is endogenous holds more water.

Results

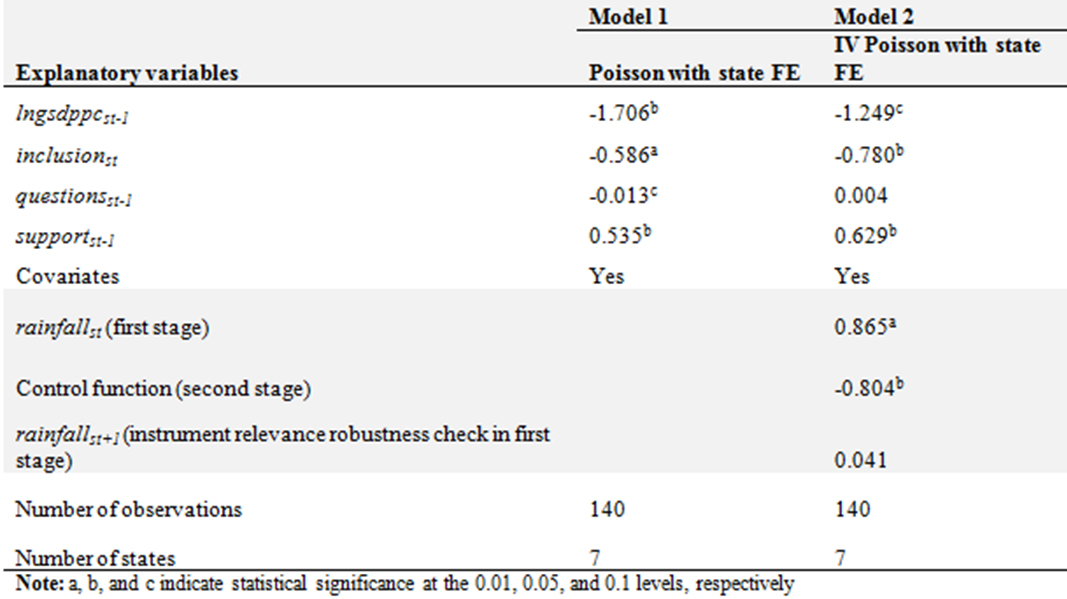

Two sets of Poisson regression outputs with alternative specifications are exhibited in Table 2. Model 1 presents the base Poisson FE model estimates of equation 1. It is seen that economic development leads to a reduced number of incidents of killings due to insurgencies. This relationship is statistically significant, thereby lending credence to Gurr’s theory of relative deprivation in the NER context. Additionally, the inclusion of an MP from the NER in the Union Council also leads to a statistically significant decline in incidence of killings at all conventional levels of significance. Enhanced national-level political participation, proxied by the number of questions asked, decreases the human cost of insurgent activities at a 10 per cent level of significance. Finally, majority ethnic group support for rebel factions is significantly associated with increased incidence of casualties due to insurgencies at a 5 per cent level of significance. The results thus far are congruent with a priori expectations.

Model 2 displays the Poisson FE model with per capita income instrumented by rainfall variation. It demonstrates a statistically significant negative association between economic development and the incidence of killings. However, when accounting for the endogenous relationship between economic growth and insurgency, we find that the null hypothesis of no significant effect of increased participation cannot be rejected. One possible explanation for this is that, while the number of questions asked by MPs is certainly a valuable measure for participation, it may not encapsulate the full ambit of what ‘political participation’ entails. Other forms of participation, such as policy advocacy, legislative initiatives, and resource allocation decisions, among others, could have a more direct and substantial influence on the insurgency landscape. A future area of research could investigate these other measures of participation and their effect on insurgencies. Data scarcity for these measures currently constitutes a limitation for this paper. Results for inclusion and support remain consistent with the previous model, demonstrating strong support for the involvement of NER leaders in national-level politics and alleviation of community support for rebel groups as effective measures to reduce casualties resulting from insurgencies.

Table 2: Regression outputs

Furthermore, the estimated coefficient on rainfall in the first-stage regression (equation 2A) was found to be positive and statistically significant at all conventional levels of significance in model 2. This offers support to the ‘relevance’ of the instrument. Following the methodology prescribed by MSS, I conducted a “false experiment” wherein I replaced current rainfall variability with future rainfall variability at the first stage and computed the same regression. The coefficient on the one-year lead rainfall-which should be orthogonal to current per capita income-was found to be statistically insignificant, providing added evidence of the instrument’s relevance for addressing endogeneity concerns. However, the instrument’s overall appropriateness rests on two other criteria. The first is the ‘exogeneity’ criterion, which states that the instrument itself should not suffer from endogeneity. To address this, I posit the theoretical justification that rainfall variability is solely affected by natural factors, and is, therefore, the ideal ‘exogenous’ variable for this analysis. The second is the ‘exclusion restriction’ criterion, which means that rainfall variability can affect insurgencies only through its relationship with economic growth and not through other channels. This assumption is challenging to satisfy, and I acknowledge that there could be alternate avenues through which rainfall variability could impact the frequency of insurgency incidents that result in casualties. While this poses a limitation for this research, I nevertheless performed a few robustness checks. For brevity’s sake, I excluded these results from this paper. First, I found that rainfall variability has no significant association with the states’ social allocation ratio (the ratio of social sector spending to total expenditure) when controlling for the full series of covariates, suggesting that rainfall does not affect the states’ fiscal spending on basic services such as health and education, which could theoretically propel conflict. Second, following MSS, I replaced per capita income with rainfall variability and ran the base model in equation 1, thereby directly including rainfall as an explanatory variable. The motivation behind this, as explained by MSS, is that rainfall might directly cause more insurgencies by destroying enabling infrastructure such as roads, which in turn might make it more expensive for the government to restrain rebel outfits. However, the effect of rainfall was found to not be significantly different from 0, thus mitigating this possibility.

Finally, the estimated coefficient on the endogenous control variable was found to be statistically significant at a 5 per cent level of significance in Model 2. This signifies strong evidence that per capita income is indeed endogenous, thus rationalizing the employment of the IV strategy.

Conclusion

To summarize, these results illustrate that, even when adjusted for the endogeneity of economic growth, economic growth has a statistically significant negative relationship with the incidence of killings caused by insurgencies. However, the effect of questions raised by MPs concerning Northeast development and tribal affairs on the incidence of killings caused by insurgencies is statistically insignificant. Meanwhile, the impact of the inclusion of MPs in the Union Council and ethnic community support for insurgency outfits are robust across both specifications. The former lessens the incidence of fatalities due to insurgencies, while the latter augments it.

Nonetheless, we must interpret these results with caution, and be cognizant of data limitations, bias due to omitted variables (such as the strength of law enforcement and quality of institutions), and measurement errors. The relationship between economic growth and the incidence of insurgency is a deeply nuanced one, especially in NER. Hence, there is a need to drive much-needed future research into one of the oldest theatres of insurgency in the world.

Drawbacks aside, this paper contributes to the extant literature on political violence in the Northeast region by focusing on the factors influencing the human cost of insurgencies and through its employment of an instrumental variable methodology. It provides corroboration on the soundness of rainfall variability as an instrument for economic growth in the NER context. Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, the use ofthe panel Poisson control function technique is distinct in this domain.

Overall, the findings indicate a pressing requirement for policymakers to spearhead initiatives to foster economic growth, promote political inclusion and participation and address community grievances to create an environment conducive to peace, stability, and development in the region. Social welfare, employment generation programs, and investments in infrastructure, along with community engagement and the mainstreaming of NER’s political participation at the national level, are all imperative efforts that policymakers should undertake. Furthermore, international organizations could take more proactive steps in terms of humanitarian aid, mediation and facilitation, advocacy and awareness-building, and development assistance in NER. It is crucial to cultivate an atmosphere of social cohesion and take more concerted efforts to accelerate social, economic, and political progress in the region.

Bibliography

Agrawal, N., Bhogale, S., Bose, A., Kumar, M., Malik, D., & Mishra, O. (2021). TCPD–ICoM: Indian Council of Ministers Dataset 1.0. Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University.

Asharaf, N., & Viswanathan, B. (2022). Socio-economic factors and conflict in North-easter region of India. Madras School of Economics Working Paper Series.

Baruah, S. (1989). Minority policy in the North-East: Achievements and dangers. Economic and Political Weekly, 2087-2091.

Bhattacharyya, R. (2018). Living with armed forces special powers act (AFSPA) as everyday life. GeoJournal 83, no.1, 31-48.

Bhaumik, S. (2004). Ethnicity, ideology and religion: Separatist movements in India’s Northeast. Religious radicalism and security in South Asia, 219-244.

Bhogale, S. (2019). TPCD-IPD: TCPD Indian Parliament Dataset (Question Hour) 1.0. Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University.

Brahmachari, D. (2019). Economic Determinants of Ethnic and Insurgent Conflict: an empirical study of northeast Indian states.

Cederman, L.-E., Wimmer, A., & Min, B. (2010). Why do ethnic groups rebel? New data and analysis. World Politics 62, no. 1, 87-119.

Cline, L. E. (2006). The insurgency environment in Northeast India. Small Wars & Insurgencies 17, no. 2, 126-147.

Government of India. (2008). Capacity Building for Conflict Resolution.

Gurr, T. (1994). Peoples against states: Ethnopolitical conflict and the changing world system: 1994 Presidential Address. International Studies Quarterly, 38(3), 347-377.

Gurr, T. (1970). Why men rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Haokip, T. (2012). Political integration of Northeast India: A historical analysis. Strategic Analysis, 304-314.

Hazarika, S. (1995). Strangers of the Mist: Tales of War and Peace from India’s Northeast. New Delhi: Penguin.

Laqueur, W. (1999). The new terrorism: Fanaticism and the arms of mass destruction. Oxford University Press.

Miguel, E., Satyanath, S., & Sergenti, E. (2004). Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Journal of Political Economy.

Piazza, J. A. (2012). Types of minority discrimination and terrorism. Conflict Management and Peace Science 29, no.5, 521-546.

Skocpol, T. (1977). States and Social Revolutions.

Vadlamannati, K. C. (2011). Why Indian men rebel? Explaining armed rebellion in the northeastern states of India, 1970-2007. Journal of Peace Research, 605-619.

Waterman, A. (2020). Counterinsurgents’ use of force and “armed orders” in Naga Northeast India. Asian Security.

Wooldrdige, J. (1999). Distribution-free estimation of some nonlinear panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 77-97.

Wooldridge, J. (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. The MIT Press.

Wucherpfennig, J., Metternich, N. W., Cederman, L.-E., & Gleditsch, K. S. (2012). Ethnicity, the State, and the Duration of Civil War. World Politics, 79-115.

Aditya Kurup

Aditya Kurup is an economist and public policy analyst currently engaged in the development sector in India. He holds a Master’s degree from OP Jindal Global University. His research interests lie at the intersection of development economics, politics, and applied quantitative methods.