Evaluation Summary Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao (2015-2022)

A Government of India (GoI) Intervention to let girls be born, nurtured and educated.

Beti Bachao Beti Padhao: Why are we still talking about it?

India is on its way to becoming the fastest-growing economy in the world and will surpass China as the most populous country this year, as per the latest reports. Experts suggest that India needs to drive its economic growth along an inclusive development route. It must use this challenge and opportunity to unlock its demographic potential across all sectors. Part of this involves bringing more women into its workforce and ensuring equitable access to basic needs such as education, employment, and health. This is also imperative to fulfil its promise to “leave no one behind”, as part of its commitment to the 2030 Agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals. Yet here we are, still struggling to balance our country’s sex ratio at birth and trying to protect the basic right of a girl child to live with dignity and equal opportunity in this country.

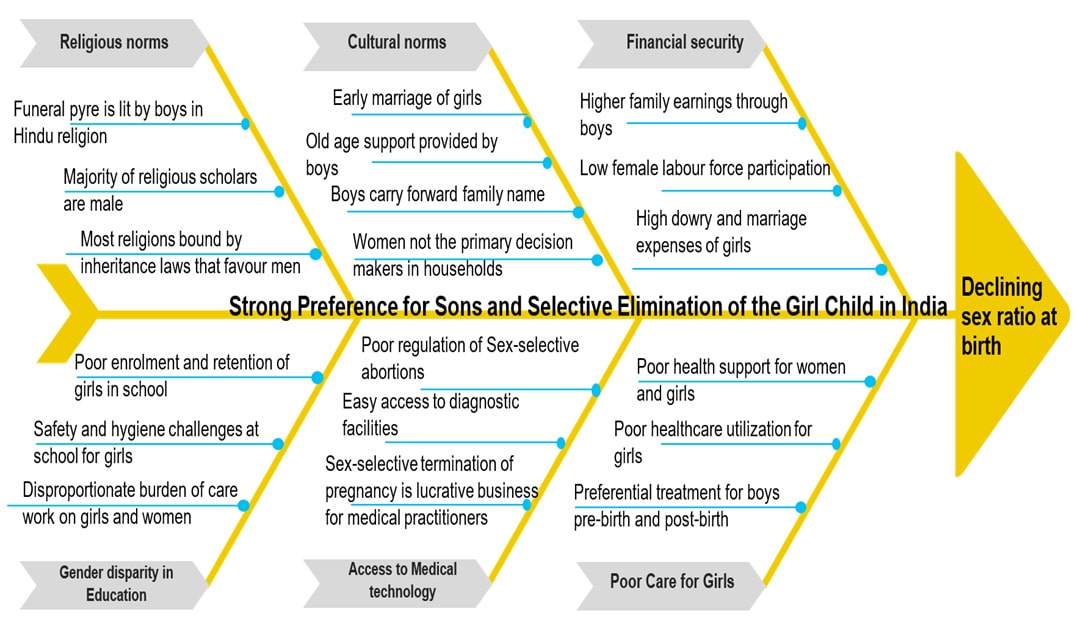

A skewed child sex ratio (CSR) in India has been reported and studied by several authors since the early 20th Century, starting from the first Census in 1871. A strong son preference emerges as the primary cause for the neglect of the girl child in patrilineal and patrilocal Indian societies, leading to a high 0-4 year girl child mortality rate. In the 1990s, this problem was further aggravated by the rampant proliferation of medical technologies which facilitated illegal detection of the sex of the fetus. The “Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act” of 1994 was the first direct law in India to curb sex-selective abortions, later revised in 2003 as Pre-Conception and Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques (PC & PNDT) Act. This Act made the record keeping of diagnostic tests mandatory and restricted use of these tools by registered centres and qualified persons only. However, despite these legal measures, several reports continued to highlight a severely declining pattern of CSR in India, which came to its lowest in the Census Data of 2011. Some reports attribute it to a slack in implementation of the PC-PNDT act or the delay in judicial convictions, however, a detailed study of the issue reveals several inter-related factors that perpetuate the strong son preference, leading to an increase in the selective elimination of the girl child in India.

The following figure depicts the various factors via a root cause analysis of this issue using a fishbone diagram:

Root cause analysis for BBBP

Given the need for an intervention that addresses the pervasiveness and complexity of the problem via multi-stakeholder action and multi-sectoral approach, the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao (BBBP) scheme was conceptualised. Launched in January 2015 by the Government of India, the BBBP was announced as a tri-ministerial effort (Women & Child Development, Human Resource Development, and Health & Family Welfare) to

- Ensure survival, protection, and education of the girl child;

- Create equal value for the girl child through social mobilisation, community engagement and sensitisation of stakeholders.

The scheme was launched in 100 critical districts in 2015, followed by a pan-India expansion in 2018.

Since its launch, several news reports and reviews of the BBBP scheme have tried to reflect on its progress and impact at different stages. While many of them make contradictory conclusions about the effectiveness or impact of the scheme, there is largely a consensus on the scheme’s high relevance and low efficiency. This independent study, by policy scholars of the Indian School of Public Policy, verifies and presents an updated perspective on its progress so far and key areas of improvement for the future.

Does this intervention fit?

In line with the international commitments and rights of the girl child to life, survival, protection, education, and participation underscored in SDGs1 , CRC2 and CEDAW3 , BBBP scheme has been a unique initiative for dealing proactively with discrimination against the girl child. Apart from the constitutional provisions that talk about equal rights of women and children, the National Development Agenda4 also reinforces the relevance of an intervention like BBBP. The scheme is high on coherence with other schemes such as Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, National Health Mission, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (Pregnant and Lactating Mothers), One Stop Centre (all women and girls), and Sukanya Samridhhi Yojna. Overall, this intervention has been useful as an overarching theme that complements other schemes and influences various stakeholders to focus on gender issues in development. It displays high convergence in the use of resources, administration structure and convergent action by various ministries.

Are we achieving any results?

Image Source: www.tribuneindia.com

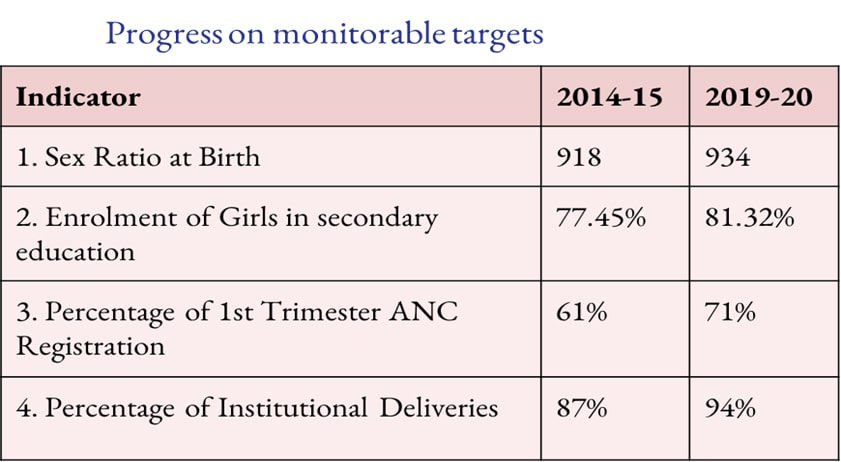

The scheme has brought the issue of gender discrimination into focus. It has resulted in improvement of all major indicators5 such as CSR, enrolment of girls in school, percentage of institutional deliveries etc over the years. However, progress has been slow. Lack of disaggregated data, poor monitoring, poor expenditure planning and side-lined focus on sectoral interventions have hindered the desired change and consistent results across states. If we look at the measurable impact of the scheme in the immediate five years of its implementation, there are several reports like data from the Civil Registration

Image Source: www.tribuneindia.com

Systems in various districts highlight the stabilisation of the sex ratio at birth. There has been remarkable progress in some of the most critical districts like Mau (Uttar Pradesh), Karnal (Haryana) and Patiala (Punjab), to name a few. Early registration of pregnancies and the number of women opting for institutional births has reportedly improved since the launch of this scheme, as has the enrolment ratio of girls in secondary education.

The celebrations, however, still have to wait as the progress has not been consistent year-wise and across districts. Also, we do not have enough data to assess the impact of the scheme on girls from marginalized communities and the extent to which the scheme is enabling educated girls and expecting mothers to participate in the decision-making process of their own lives and families. It should also be noted that the intervention mostly focuses on rural areas despite strong evidence and experience of the practice of female foeticide prevailing in urban areas. In such areas, wealthy and educated families fare high on all the three factors that perpetuate sex-selective elimination of the girl child- willingness (son preference), ability (better access to medical technology for sex determination), and readiness (due to smaller family size).

How well is the scheme being managed?

The scheme has been rated high on convergence as it uses existing outreach and implementation systems (such as Panchayats, ASHAs/Anganwadi workers etc) and is executed in collaboration with various other departments. Despite this, the scheme has been unable to use the allocated resources efficiently. In 2017-186 , its audit report highlighted the under-utilisation of funds and disproportionate spending on media and advocacy alone. Field surveys and interviews with stakeholders revealed that there is a lack of clarity amongst the ground-level functionaries on their specific duties or tasks under this scheme. This results in a lack of effective monitoring to ensure efficient resource management.

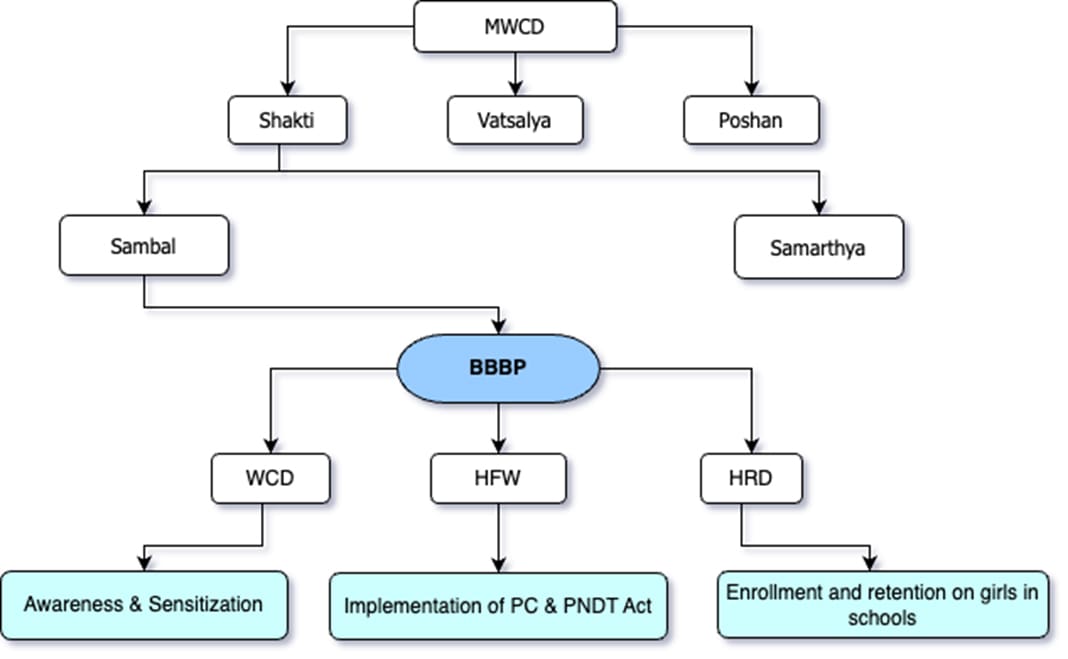

Based on stakeholder feedback and audit, vital revisions were made in the implementation strategy of the scheme from 2022 onwards. The government announced a greater focus on sectoral interventions and zero-budget advertising under this scheme, in the Parliament. BBBP was approved as a component under the Sambal sub-scheme of Mission Shakti in the 15th Finance Commission. The Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship and the Ministry of Minority Affairs have also been added as partners with a view to promoting skill development and employability of girls.

BBP location and structure as part of the MWCD programs. Reference: https://wcd.dashboard.nic.in/

Can we make it better?

Image Source: www.tribuneindia.com

While the original agenda of the scheme was to address the issues that threaten the rights of a girl child over a life cycle continuum, the design of the scheme does not address the concerns of the key stakeholders at different stages of the life cycle of a girl– from the womb to a young adult. A detailed stakeholder analysis also reveals that the scheme gives urgent attention to the community and secondary stakeholders but it is unclear

how it would empower the mothers to make better choices.

There is another major lacuna in the scheme design—it does not have precise (exclusive and exhaustive) indicators for measuring the actual outputs and outcomes of the intervention. It needs to revisit the measurable targets, as the declining child sex ratio is only a symptom of the real problem. There are several underlying factors that perpetuate gender bias against the girl child like lack of financial independence, early marriage, poor participation in decision-making, and so on. We need to ask ourselves that even if the number of female children to male children is brought up to the suitable ratio, will it make daughters as desirable in a family as sons? What will make girls be seen as an asset to the family, instead of a financial or social liability?

Recommendations

(Beti Bachao, Padhao aur Sashakt Banao)

The BBBP scheme with its creative communication and awareness strategies and multi-sectoral initiatives has the right approach. Yet, the design of the scheme falls short of addressing the root cause of the issue of sex-selective elimination of the girl child. From an approach perspective, the scheme is well-intentioned in its attempt to address the three interlinked goals of Prevention of undesirable behaviour, Adoption of desirable behaviour and Creation of an enabling environment to sustain the positive shift in behaviour. However, from an implementation perspective, much needs to be done. Apart from education, financial independence, family dynamics and greater social/political participation of girls are key factors in systematically reducing the gender bias against them at a young age and creating an equitable growth environment for all.

Some key suggestions that came up as a result of this evaluation are as follows:

Goals

- Redefine goals into short-term, mid-term and long-term (based on Focus Group Discussions with communities)

- Focus on enabling women to participate in decision-making regarding the future of their girl child

Scope of Intervention

- Increase focus on Urban areas and Vulnerable Groups

Monitoring

- Identify exhaustive and clearly defined indicators for measurement of outputs (Survival, Growth, Education, Skill development, Jobs creation, Employment/Entrepreneurship, Representation & Participation in Public Events and Workforce )

- Set clear responsibilities for each ministry/implementation partner via a Theory of Change7 approach to make them accountable.

- Disaggregated data collection (Male-Female, Urban-Rural, vulnerable groups etc)

- Common platform linking all data sources – database of progress on all aspects of girl child welfare (beti kosh)

Implementation

- Incentivise public-private partnerships for executing community-level activities

- Funds can also be utilised for:

- Basic literacy for women

- Use of technology, e.g. mobile phones, for monitoring and awareness–Training of stakeholders for the same

- Complaint registration platforms at each level of intervention–offline and online

- Empowerment of frontline workers to build greater ownership/stake in the intervention (participatory approach rather than a top-down approach as they can bring more localised and customised solutions under a broader guideline)

- Regular feedback from the public, the primary stakeholders – young parents and the girl child, and frontline workers on challenges and progress

- A lot of prejudice, discrimination8 and violence is a result of objectification or dehumanization8 of the person or group. Subtle Humanisation of the Foetus (Naming, showing images, etc) may be a useful approach in helping parents/families connect with the unborn child and make a responsible choice.

All said and done

There have been several legislations since independence that address the issues related to the protection of the rights of the girl child. However, laws alone do not solve such issues. Just getting the child sex ratio right is not going to make girls desirable as equal participants in society. What is required is a social awakening and collective will to end this menace. That being said, future evaluations must also attempt to answer:

- Scalability: What are the lessons from this experience that can be replicated for other schemes, especially from the social behaviour change perspective?

- Scope: Why is the major focus only in rural areas, despite the fact that the Child Sex Ratio is worse in Urban areas?

- Convergence and Accountability: How has this scheme changed the way the government approaches a complex social issue? Who is accountable for favourable or unfavourable progress at each stage?

- Sustainability: What would have happened if this intervention was not in place? What if it’s no longer in place? What do the collective indicators and experiences tell us about long-term behaviour changes towards women and of women?

- Patronising or Empowering: Does the communication campaign project women as mere receivers of the protection or welfare services or are we sufficiently emphasising their rights, voice and entitlements as equal citizens and human beings?

We need to address the various strands that have created this embarrassing and damaging social fabric where societies sanction the killing of daughters in order to preserve tradition or self-interest. Having met some initial success, this intervention should be redesigned to address all forms of violence and discrimination against women holistically. A life cycle continuum approach is useful only if it helps in understanding and designing step-by-step interventions at each stage–from the unborn child to adulthood. It should be designed in a way that bridges the gaps between any two life stages of the child by ensuring continuous support and an equitable environment for growth.

Revision of indicators, creation of a comprehensive gender database, and development of efficient reporting capabilities in the field are good starting points from a policy perspective. It is also an opportune time to use the momentum created by this intervention and focus on increasing the agency and autonomy of women in families and public spaces.

More importantly, it should be the parents (and especially the expecting mother) who ought to be empowered as the decision-makers regarding the future of their unborn/infant child. The state and society can help by working towards creating an environment where they can make the right choice, without fear, bias or prejudice.

FAQs

What is the main aim of the “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” Intervention?

The BBBP was announced as a tri-ministerial effort (Women & Child Development, Human Resource Development, and Health & Family Welfare) to

- Ensure survival, protection, and education of the girl child;

- Create equal value for the girl child through social mobilisation, community engagement, and sensitisation of stakeholders.

Why is India still talking about Beti Bachao, Beti Padao?

India continues to struggle to balance our country’s sex ratio at birth and try to protect the basic right of a girl child to live with dignity and equal opportunity in this country.

Has the BBBP Scheme proved to be impactful?

The scheme has brought the issue of gender discrimination into focus. It has resulted in improvement of all major indicators5 such as CSR, enrolment of girls in school, percentage of institutional deliveries, etc over the years. However, progress has been slow.

Is there a way to make it better?

There are several underlying factors that perpetuate gender bias against the girl child like lack of financial independence, early marriage, poor participation in decision-making, and so on. We need to ask ourselves that even if the number of female children to male children is brought up to the suitable ratio, will it make daughters as desirable in a family as sons? What will make girls be seen as an asset to the family, instead of a financial or social liability?

Endnotes

1. Sustainable Development Goals

2. Convention on the Rights of the Child

3. Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

4. A 15-year-long vision set by the NITI Ayog from 2017-18 to 2031-32, which has identified women and child welfare as one of the priority sectors

5. Source : https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1691725

6. Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao | 80% of funds spent on media campaigns, says Parliamentary Committee – The Hindu

7. Theories of change depict a sequence of events leading to outcomes; they explore the conditions and assumptions needed for the change to take place, make explicit the causal logic behind the program, and map the program interventions. Stakeholders can be brought together to develop a common vision for the program, its goals, and the path to achieving those goals (Gertler, Paul J., Sebastian Martinez, Patrick Premand, Laura B. Rawlings, and Christel M. J. Vermeersch. 2016. Impact Evaluation in Practice, second edition)

8. Dehumanization is the denial of full humanness in others and the cruelty and suffering that accompanies it. As a process, dehumanization may be understood as the opposite of personification, a figure of speech in which inanimate objects or abstractions are endowed with human qualities

Anjali Agarwal

Anjali Agarwal is a management professional and a development practitioner currently serving as a business strategy consultant for an organisation that helps mid-size companies solve their complex organisational issues.

Meeta Rathi

Meeta Rathi is an engineer and PG in Economics who has worked as a data analyst, product manager, and research associate with simultaneous voluntary engagements in education-focused organizations.

Dr. Monica Sabharwal

Dr. Monica Sabharwal has a graduate degree in Dentistry and PG in Management, Public Health and Nutrition. She has led projects in healthcare and education with Government of Punjab & Haryana and conducted research studies as a consultant for few other healthcare organisations.

All three of them successfully completed the Lokneeti course of ISPP (Certificate in Policy, Data and Behaviour Change) in March 2023.