What the Tuberculosis Foreign Aid Trajectory Tells Us about COVID-19: An Analysis

In the wake of COVID-19, our global public discourse and policy execution measures have frantically adopted “unprecedented” into routine vocabulary. As the virus rapidly pushes globally interdependent socio-economic systems into isolation, the notion of “public” in public health is simultaneously evolving. While our pandemic-centric histories do not deliver frameworks of certainty, they leave us with room to assess rapid, delayed and continued global action. The manner in which nations choose to respond to global public crises is a cumulation of their domestic infrastructure, national security policies, international economic interdependence and dynamic foreign relations. While these indicators are similar throughout the world, the values they occupy vary significantly across different socio-economic profiles. This is not to simply say that COVID-19 is a virus that hits everyone differently; it is to note that this pandemic’s consequent externalities will be different, spatially and temporally. For instance, 25th March 2020 marked the day India announced its first nation-wide lockdown in the fight against COVID-19. To see it antedate yet another World Tuberculosis Day (24th March) significantly highlighted the material reality of borders in borderless crises. Owing to the aforementioned differences, foreign aid is a commonplace policy response that countries adopt in times of any public health crisis. While it creates enough room to speculate about political hegemonies and diplomacy, it is almost always viewed as a functionary in providing immediate relief. In order to better understand the role of international cooperation and sustained interdependence in crisis mitigation, this article charts multilateral and bilateral monetary foreign aid delivery for COVID-19 and Tuberculosis. These trajectories, coupled with geopolitical paradigm shifts, lay implications for building global and domestic health crises mitigation capacity.

Tuberculosis and COVID-19: Is a Comparison Warranted?

Comparing TB as it exists today to the Coronavirus would be a futile exercise. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (TB) was first isolated over a hundred years ago and has evolved to being one of the top 10 infectious diseases of the world. 1,2 It’s average death count since 2016 stands around a staggering 1.5 million lives lost per year. COVID-19, as all-encompassing as it is, has made a considerable yet smaller dent at 3,55,305 deaths worldwide as of the 28th of May 2020.3 Having said that, what is of most merit to our analysis is the noteworthy similarity that ties TB and COVID-19 together, i.e. their initial disease burden on High Income Countries (HICs). This specific context setting allows one to make predictions for future patterns of COVID-19 relief aid.

Additionally, popular literature on epidemiology, civil society organisations and the development sector investments. support the comparison between TB and COVID-19. Therefore, our selection of TB has not been arbitrary. The authors argue that COVID-19 cannot be effectively compared to other pandemics and/or epidemics. The word “unprecedented” drives the picture home. Ebola, a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,”was felt exceedingly fleetingly around the world as it predominantly made its effects felt in West Africa. Similarly, the Zika fever, another epidemic as recent as 2015, originated in Brazil and spread to only parts of South and North America.4,5 However, with both these outbreaks, and others in modern history, our societies have not witnessed the implementation of such lockdown-adjacent policies. Therefore, comparing these epidemics to COVID-19 would not yield any foresight into the behaviour of political economies, foreign relations or prospects of foreign aid.

Charity v/s Policy: Foreign Aid Relevance

While foreign aid is altruistic and compassionate at face value, it has a deep-rooted history in “hard-headed diplomatic realism” and domestic economic considerations. In diplomacy, foreign aid is an archetypal tool for “soft-power” building.6 Economically speaking, the push for foreign aid began due to the belief that the key to triggering economic growth worldwide was to pump money into factories, public and market infrastructure.

During health crises such as COVID-19, however, foreign aid takes on an additional short-term objective, i.e. providing ‘worse-off’ countries with immediate funds to bolster their public health capacity and efficiency of state response. The word ‘additional’ here is of value to our analysis, this addition is an insurance investment against a probable global spill-over of mishandling in systems of Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs).

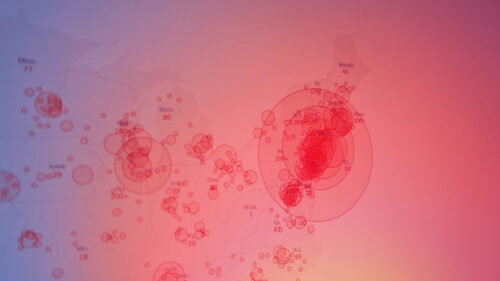

Therefore, it is prudent to study the trajectory of foreign aid movement as it has a legitimate impact on the LMICs’ capacities to mitigate crises. A close study of TB-aid highlights how a disease that is largely curable persists to this day in the LMICs. In the face of COVID-19’s disastrous uncertainty, this analysis becomes increasingly relevant. The following figure maps a brief history of noteworthy and aid adjacent events in modern TB history.

A Brief Analysis of the Long History of TB-Aid: Establishing Context

Figure 1: Recent Trajectory of Foreign Aid Activities Against the TB Pandemic7

As depicted in Figure 1, despite TB’s long history, it was only declared a health emergency by the WHO in 1993. Notably, it was the first infectious disease to be declared so. TB began its journey in the HICs, ravaging politically significant locations such as New York before tapering out of public discourse in the mid-1990s.8 During that time, the HICs formulated strong initial global and domestic health policy pushes to combat TB. As these policies showed favourable and successful domestic results, the acceleration in case detection moved to the LMICs – primarily driven by India in 2000 and China in 2002. Regardless, only 7 out of 22 High-Burden Countries or HBCs, (countries with the relatively highest absolute values for total estimated TB cases), met their target of 70% reduction by 2005. Simultaneously, the estimated TB case peak, the global reported death burden was still high at 1.6 million people.9 However, notably, the HICSs reported a trend shift in infected persons from nationals to immigrants, or primarily “foreign-born or foreign citizens.”10 As the HICs’ death toll started declining (to a significantly reduced figure of 515 deaths in 2017 in the United States), and 95% of all TB cases shifted to the LMICs, the global political commitment from the HICs fell too. This is particularly alarming because, in our global economies, the pattern of foreign over national infection is a national security threat to the HICs too.

TB’s disease burden shift in the early 2000s, prompted international organisations and co-operations of the LMICs to improve their TB response and reduce the dependency on aid, technology and healthcare innovation from the HICs. Seeing how large HIC donors to TB relief, such as the US or Canada, had rapidly started scaling back on overseas aid during this time, this was a timely yet prefatory shift in global order. In particular, the association of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) started stepping into spaces of research and domestic aid investment. They accounted for 53% of the available funding in 2019, and 95% of their funding came from domestic sources.

We must note that it has been established that TB is intricately linked to poor health conditions such as malnutrition, alcoholism, HIV and diabetes – these are afflictions more pervasive in the LMICs than the HICs.11 So, even though the aforementioned global paradigm shift provided the LMICs an opportunity to invest in themselves. Their disease burden is still significantly high and public health capacity is still significantly low. For instance, according to the 2019 Global Tuberculosis Report, India has the highest number of Multi-Drug Resistant TB (MDR-TB).12 This is also evidenced by the fact that by 2009, Asian and African regions constituted 86% of TB cases globally. However, apart from a few emerging economies, such as India or China, international donor funding remains crucial for the other LMICs.13 Therefore, even though focus has been placed on reach and research, quality of treatment remains to be a significant threat.

Despite increased global urgency for TB eradication, between 2015 and 2018, the aggregate reduction in cases was only 11% against the target of 35%.14 Here, it has been accounted that this figure of 11% does not cover unreported cases. What is of immediate consequence to public health in 2020 is the increasing lack of measures to quantify the threat from unexamined deaths during COVID-19.

As global systems prepare their COVID-19 economies, they have begun acknowledging that “post” COVID-19 is a far-off time. Currently, there is no way to assess and factor future COVID-19 treatment, vaccination and immunity failures and accessibility. What is also of immense policy concern to public health officials and civil society members is the rapidly changing status of TB. The threats of increased, unreported and mutated TB cases, and potential loss of progress of decades of investment in TB eradication, during the various COVID-19 “lockdowns,” are increasing. WHO has already estimated a 75% decrease in weekly detection of TB cases in India, the country with the largest global TB burden today.15 While this estimation has alarming conclusions of its own, it massively complicates and weakens India’s domestic COVID-19 mitigation capacities.

The Long Future of COVID-19: Integrating What we Know

At present, with COVID-19 we see a similar “area of spread” trajectory, origin in Wuhan province spread first to the economically “well-off” countries such as Italy, Spain, Germany, the United States. Currently, the global epicentre has moved to the “worse off” South American region, specifically Brazil, Peru and Chile.16 Its progression to the LMICs has been gradual and has had some degree of forewarning. Both diseases’ propensity to overwhelm national health systems has been analogous: By March 2020, the news had broken that due to coronavirus, Italy had run out of beds in intensive care units in the most hard-hit regions.17 Similar shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), masks, medicine, ventilators and more were reported all the way from New York to Mumbai.18,19 Likewise, TB at its peaks, hit minority groups with higher incidence and record cases in clusters. It has become evident that low-income areas, even in HICs, have stressed public health systems which follows that during a TB spike, these systems came under more duress.

Evidently, the impact of foreign aid has alleviated the burden of TB on global public health systems. As we have just analysed, the HICs rallied together since the 1990s to invest billions in fighting TB around the world. However, to better understand the future of COVID-19 relief aid for the LMICs, it is important that we do not misconstrue systemic efforts and participation of the HICs as solely altruistic in nature. Patterns of increased global mobility made it imperative for the HICs to view TB in its global context. COVID-19’s “unknown” vulnerability presents the same problem to the HICs.

Initial Aid v/s Sustained Aid: A Problem of Misinterpretations and Predictions

Foreign aid in health is unique when compared to other aid investments as its sole purpose is to associate a better image of the giver countries for the recipient countries. We have repeatedly established that the changing nature of foreign aid activity is a direct consequence of the shift in TB’s disease burden from the HICs to the LMICs. With COVID-19 too, there cannot be a zero-sum debate between investing money locally versus sending aid to foreign countries. This, we can conclude, has been one of the driving forces for why the Trump administration, an administration Figure 1 shows to have significantly tightened its foreign aid purse strings in 2016, is currently pledging $5.9 million to India; $18 million of Afghanistan; $15 million to Pakistan; and an overall $775 million in emergency health, humanitarian and second wave economic assistance that will assist over 120 countries in combating COVID-19.20

The generosity in foreign aid may also be a reflection of a better understanding of the nature of global pandemics among the HICs – to treat it domestically, they will have to address it internationally. The UN has already warned developed nations that COVID-19 will “circle back around the world” in its second wave if they fail to equip poorer nations in managing the pandemic.21 Multilateral agencies are collectively agreeing that the unstable environments of LMICs are generating higher collateral and human costs. Therefore, in terms of prioritisation, a considerable portion of the aforementioned aid is routed to LMICs. The UK is another HIC leading this effort by allocating nearly $200 million aid solely to developing countries, of a total of $744 million aid given worldwide. The UK is currently one of the biggest donors to combat the global pandemic.

As forecasted by Figure 1, fissures in HICs commitments to foreign aid for COVID-19 mitigation are expected. However, we are noticing a quicker movement toward ‘self-preservation first’ from states like the US. Multiple countries, France, Canada, Brazil, Germany and Barbados, have accused the US of diverting medical supplies to itself by price-gouging.22 The United States has similarly strong-armed India into procurement of experimental medication to treat COVID-19 and then diverted medical supplies en route to India a short week after.23 This instinct for “America First,” that the Trump administration is showing, is symptomatic of the general foreign policy stance this government has taken since 2016. In sharp contrast, previous US administrations were considered leaders in the global relief efforts to combat TB. Apart from monetary foreign aid, the US had extended foreign aid in kind too – the US supported the Government of India’s national TB program by leveraging local experts and extending technical resources as well. It is ironic to note that the official USAID website highlighting said bilateral relationship is titled “Championing a TB-Free India.” The USA’s decision to temporarily withdraw 15% funding from the WHO has also come across as a shock to member countries and is again evidence of the nationalistic and self-serving attitude the United States has taken to combat a global struggle.24 This might also hinder the formation of effective multilateral efforts (such as the Global Fund) which were instrumental in procuring aid and sanctioning projects to curb TB.

Therefore, current geo-politics seem to predict that the future trajectory of global efforts in combating COVID-19 might indeed observe brief collaboration, akin to what the TB crisis observed for decades. However, despite the need of the hour, polities might soon devolve into self-serving interests. While one may want to argue that ‘every country for themselves’ is a reasonable foreign policy stance to take during an ‘unprecedented’ global pandemic. It is indisputable that much like TB, the second, third, or even a wavering fourth wave of COVID-19 will impact the entire world (HICs alike). Furthermore, the manner in which COVID-19 will leave its residual externalities in the HICs has already started surfacing; global lockdowns of our interdependent economies have threatened globalisation. Therefore, for an HIC to justify its spirit of ‘self-preservation’ by measures such as decreasing foreign aid, is a fundamentally skewed argument. It must be reiterated that a foreign-aid package is not to be categorised as only an altruistic handout to the LMICs, it is as much for an HIC’s political interests, economic interdependence and mitigation of public health crises. Public health crises are not just a problem of today. How well the HICs include the LMICSs in their foreign aid packages will directly affect years of established global supply chains and the current achieved level of free movement of labour in the world.

COVID-19 is Atypical

We must revisit the word “unprecedented” at this juncture in our analysis. As comparable global reaction to TB has been to COVID-19, we have never witnessed such a state of global arrest and lockdown. Therefore, any speculation is incomplete without that factoring. Contrasting to TB though, the geopolitical situation of the world is unquestionably different than the late 90s and early 2000s. Therefore, the US’s populist and self-serving stance may hinder global unity in combating COVID-19. Although, multilateral blocs (that came into action much later during the TB epidemic) have been quicker to engage and collaborate during COVID-19.

With the LMICs learning from the outlined historic foreign aid trajectory, their resistance to the US’s global withdrawal has been better. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) member nations met in the early-stages of COVID-19 to formulate a joint-strategy to mitigate the effects of coronavirus in the region.25 The group formed an emergency corpus where almost all member countries pledged millions, agreed to share rapid-response teams during critical moments and initiated open-channels of communication on technical and medical resources. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is another important regional bloc where India, Russia and China consolidated the region’s efforts for a collective fight against the virus. There was also some outcry on the US’s “bullying” role which reiterates our argued paradigm shift in geopolitics.26 Here, it is imperative that we note that this is not to say all HICs are allowing their foreign policies to adopt an ‘escapist’ and ‘self-serving’ strategy. One may argue that the current shift partly owes itself to global economic deficits. However, it also owes itself to the manner in which countries are responding to the Eastern ‘origin’ of the disease. This behavioural assessment has weakened the credibility of multilateral organisations that played a significant role in facilitating TB aid, namely the WHO.

Lastly, we have also been able to observe that individual economies of the BRICS countries are managing COVID-19 significantly better than they handled TB. Their initiatives are amplified and backed by more robust economies and medical infrastructure. Vietnam, an LMIC and a country considered highly vulnerable to the pandemic due to its border with China, has been commended by the World Bank on its efforts against COVID-19.27 It is too soon to say whether this is a product of limited dependence on the HICs or a consequence of Western and Eastern ‘political split.’ However, it can be said with surety that the LMICs will need more inclusionary packages of foreign aid for sustained mitigation.

We have iterated that the extension of foreign aid by the HICs to the LMICs leads to an increase in independence of domestic control and global eradication. The former’s economies cannot discount the role of the latter’s labour, capital and market contributions. What our system can hope to learn from the drawn TB trajectory is an increased understanding of global communities. Additionally, especially for the LMICs, domestic development sectors must use this time to address trust-deficits and consequently maximise their impact. As the world acknowledges that increasing MDR-TB cases coupled with the uncertainty around COVID-19 is one of our most pressing ‘wicked problems,’ our response cannot be temporally or spatially delimited.28 Collaboration has always been a preferred conclusion in public policy discourse and literature.

Works Cited:

[1] Saleem, Amer, and Mohammed Azher. “Https://Www.bjmp.org/Content/next-Pandemic-Tuberculosis-Oldest-Disease-Mankind-Rising-One-More-Time.” British Journal of Medical Practioners 6, no. 2 (June 2013). https://www.bjmp.org/files/2013-6-2/bjmp-2013-6-2-a615.pdf.

[2] “Tuberculosis (TB).” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, March 24, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.

[3] “Coronavirus Death Toll.” Worldometer. Accessed May 28, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-death-toll/.

[4] Van-Tam, Jonathan; Sellwood, Chloe (2010). Introduction to Pandemic Influenza. Wallingford, Oxford: CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-625-9. Accessed May 26, 2020.

[5] “Zika Map – Virus & Contagious Disease Surveillance”. HealthMap. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Accessed 26 May, 2020.

[6] Dan Banik, Nikolai Hegertun. “Analysis | Why Do Nations Invest in International Aid? Ask Norway. And China.” The Washington Post. WP Company, October 27, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/27/why-do-nations-invest-in-international-aid-ask-norway-and-china/.

[7] Collective Figure References:

“Tuberculosis (TB).” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, March 24, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.

Worland, Justin. “5 Scariest Health Issues In 1900.” Time. Time, August 8, 2014. https://time.com/3086432/scariest-health-issues-1900/.

“Ending TB in India: U.S.-India Partnership: Fact Sheet: India.” U.S. Agency for International Development, November 18, 2015. https://www.usaid.gov/india/fact-sheets/ending-tb-india-us-india-partnership.

“Ending TB in India: U.S.-India Partnership – U.S. Agency …,” June 27, 2019. https://www.usaid.gov/india/fact-sheets/ending-tb-india-us-india-partnership.

Edwards, Sophie. “Ukraine’s Fight against TB Is at Risk from USAID Cuts.” Devex. Devex, June 6, 2017. https://www.devex.com/news/ukraine-s-fight-against-tb-is-at-risk-from-usaid-cuts-90425.

Igoe, Michael, and Adva Saldinger. “What Trump’s Budget Request Says about US Aid.” Devex. Devex, May 23, 2017. https://www.devex.com/news/what-trump-s-budget-request-says-about-us-aid-90342.

WHO Global Tuberculosis Report Executive Summary 2020.” World Health Organization. Accessed May 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/tb19_Exec_Sum_12Nov2019.pdf.

Schocken, Celina. “Overview of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.” Center For Global Development. Accessed May 16, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/page/overview-global-fund-fight-aids-tuberculosis-and-malaria.

“Tuberculosis Mortality Nearly Halved since 1990.” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, October 28, 2015. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/28-10-2015-tuberculosis-mortality-nearly-halved-since-1990.

Pai, Madhukar. “Time for High-Burden Countries to Lead the Tuberculosis Research Agenda.” PLOS Medicine. Public Library of Science, March 23, 2018. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1002544.

[8] Alagna, Riccardo, Giorgio Besozzi, Luigi Ruffo Codecasa, Andrea Gori, Giovanni Battista Migliori, Mario Raviglione, and Daniela Maria Cirillo. “Celebrating TB Day at the Time of COVID-19.” European Respiratory Journal, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00650-2020.

[9] Watt, Catherine J, S Mehran Hosseini, Knut Lonnroth, Brian G Williams, and Christopher Dye. “The Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis.” ResearchGate, December 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-3988-4.00003-2.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Note: Strong evidence for control of and progression to active TB from “clinical trials is lacking particularly for indigenous populations and people under the following circumstances: diabetes, harmful use of alcohol, tobacco smoking, underweight, silica exposure, on steroid treatment, rheumatological diseases, and cancer.”

“WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis Preventive Treatment.” World Health Organization. Accessed May 16, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331170/9789240001503-eng.pdf

[12] Yadavar, Swagata. “More Than Half Of India’s Drug-Resistant TB Cases Remain Undetected.” IndiaSpend, October 23, 2019. https://www.indiaspend.com/more-than-half-of-indias-drug-resistant-tb-cases-remain-undetected/.

[13] Note: The spread of reduction % was primarily a measure of rates in WHO adopted regions of Europe and Africa.

“WHO Global Tuberculosis Report Executive Summary 2020.” World Health Organization. Accessed May 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/tb19_Exec_Sum_12Nov2019.pdf.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Dutta, Sumi Sukanya. “TB Case Detection in India down by 75 per Cent during Lockdown, Could Lead to Major Spike: WHO.” The New Indian Express. The New Indian Express, May 5, 2020. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/may/05/tb-case-detection-in-india-down-by-75-per-cent-during-lockdown-could-lead-to-major-spike-who-2139577.html.

[16] “Photos: South America Is the New COVID-19 Epicentre; Brazil Worst Hit.” Hindustan Times, May 26, 2020. https://www.hindustantimes.com/photos/world-news/photos-south-america-is-the-new-covid-19-epicentre-brazil-worst-hit/photo-IoILzieL00XXxTHbGbMBuJ.html.

[17] Tondo, Lorenzo. “Italian Hospitals Short of Beds as Coronavirus Death Toll Jumps.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, March 9, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/09/italian-hospitals-short-beds-coronavirus-death-toll-jumps.

[18] “Coronavirus: New York Warns of Major Medical Shortages in 10 Days.” BBC News. BBC, March 23, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-51998429.

[19] “Coronavirus: Mumbai Hospitals Face Bed, Medical Personnel Shortage as Cases Rise.” Business Today, May 6, 2020. https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/coronavirus-mumbai-hospitals-face-bed-medical-personnel-shortage-as-cases-rise/story/403016.html.

[20] “Coronavirus: U.S. Commits over $775 Million to Help Other Countries Fight Virus: U.S. State Dept.” The Hindu. The Hindu, May 2, 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/coronavirus-us-commits-over-usd-775-million-to-help-other-countries-fight-virus-us-state-dept/article31489355.ece.

[21] “COVID-19: UN and Partners Launch $6.7 Billion Appeal for Vulnerable Countries.” The Economic Times. Economic Times, May 8, 2020. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/business/covid-19-un-and-partners-launch-6-7-billion-appeal-for-vulnerable-countries/articleshow/75618414.cms?from=mdr.

[22] Ankel, Sophia. “At Least 5 Countries – Including a Poor Caribbean Island – Are Accusing the US of Blocking or Taking Medical Equipment They Need to Fight the Coronavirus.” Business Insider India, April 7, 2020. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.in/politics/news/at-least-5-countries-including-a-poor-caribbean-island-are-accusing-the-us-of-blocking-or-taking-medical-equipment-they-need-to-fight-the-coronavirus/articleshow/75027113.cms

[23] “COVID-19: Rapid Test Kits from China Meant for Tamil Nadu Diverted to US.” The New Indian Express, April 12, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2020/apr/12/covid-19-rapid-test-kits-from-china-meant-for-tamil-nadu-diverted-to-us-2128949.html.

[24] Al Jazeera. “World Reacts to Trump Withdrawing WHO Funding.” USA News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, April 15, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/world-reacts-trump-withdrawing-funding-200415061612025.html.

[25] Desk, India Today Web. “PM Modi Leads SAARC Meet, Member Nations Start Work on Regional Strategy to Tackle Coronavirus: 10 Takeaways.” India Today, March 15, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/pm-modi-leads-saarc-meet-member-nations-start-work-on-regional-strategy-to-tackle-coronavirus-10-takeaways-1655837-2020-03-16.

[26] The Wire Staff. “SCO Meet on COVID-19: Russia, China Raise US ‘Bullying’, India Flags Terrorism.” The Wire, May 14, 2020. Accessed May 24, 2020. https://thewire.in/diplomacy/sco-meet-covid-19-india-russia-china.

[27] Le, Sang Minh. “Containing the Coronavirus (COVID-19): Lessons from Vietnam.” World Bank Blogs (blog). World Bank Group, April 30, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/containing-coronavirus-covid-19-lessons-vietnam.

[28] Note: “A wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve for as many as four reasons: incomplete or contradictory knowledge, the number of people and opinions involved, the large economic burden, and the interconnected nature of these problems with other problems.”

Kolko, Jon. “Wicked Problems: Problems Worth Solving (SSIR).” by Jon Kolko, March 6, 2012. https://ssir.org/books/excerpts/entry/wicked_problems_problems_worth_solving.